Defining The Aravali: A Doctrinal And Scientific Defence Of The Supreme Court’s Approach To Environmental Adjudication

Table of Contents

Part-A – Context & Myth-Busting

Introduction: Separating Public Perception from the Judicial Record

The recent judgment of the Hon’ble Supreme Court of India in In Re: Issue Relating to Definition of Aravali Hills and Ranges1 has triggered widespread public debate. A dominant yet incorrect public narrative suggests that the Supreme Court has “redefined the Aravali to permit mining.” However, a careful perusal of the judgment shows the opposite.

The decision neither invented a new definition nor diluted environmental safeguards. Instead, it relied upon scientific evidence, expert institutional inputs, and constitutional environmental principles to resolve decades of administrative confusion that had weakened protection of the Aravali ecosystem.

The Central Misconception

A recurring assumption underlying public criticism is that the adoption of a “100-metre rule” automatically excludes large tracts of the Aravali from protection. This assumption is flawed. The judgment does not:

- lift the prohibition on new mining leases; or

- permit indiscriminate mining below 100 metres; or

- fragment the Aravali ecosystem into isolated hilltops; or

- dilute the application of environmental statutes.

What it does is clarify the scientific basis on which the Aravali system is to be identified, so that environmental protection operates consistently rather than arbitrarily.

Part-B – Scientific & Legal Core

The Aravali Paradox: Scientific Certainty and Legal Confusion

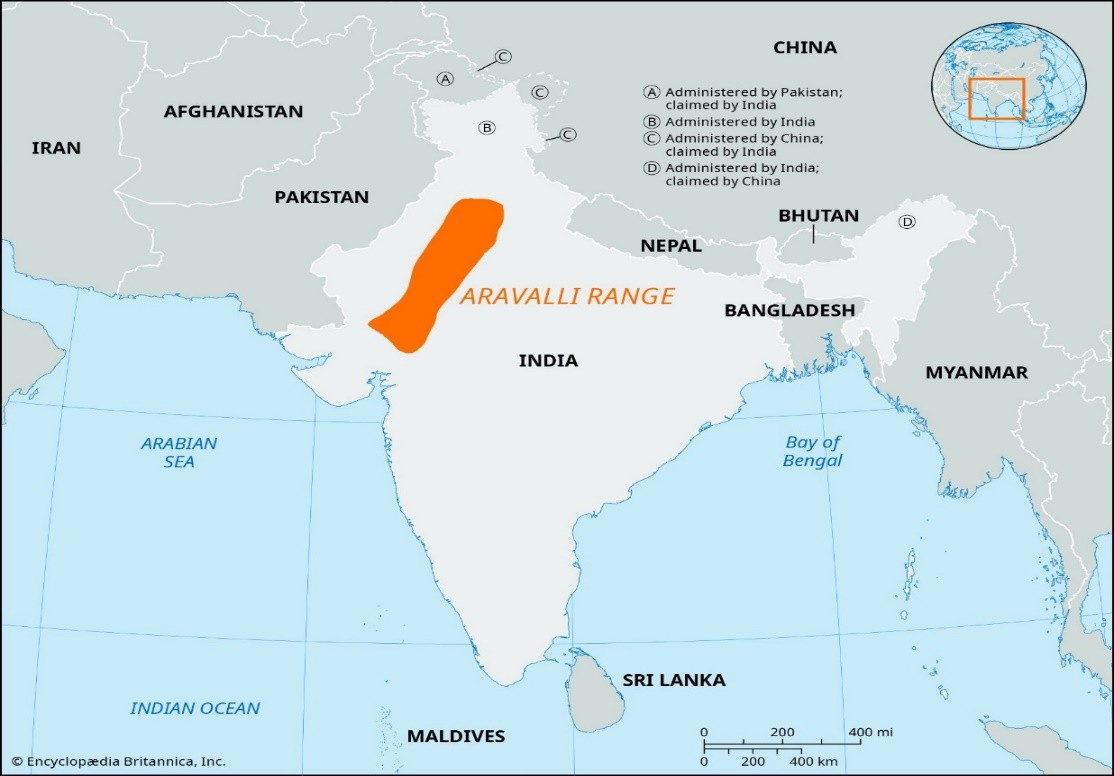

[Figures 1 & 2: Regional Context of the Aravali System

Indicative maps and satellite imagery showing the geographical spread and geological continuity of the Aravali Range across north-western India. Sources: Google Earth, Wikimedia Commons, open-access publications of the Geological Survey of India (GSI) and Forest Survey of India (FSI). Used for educational illustration.]

From a geological standpoint, the Aravali Range is amongst the oldest fold mountain systems on Earth, extending across the state of Gujarat, Rajasthan, Haryana and Delhi. The Hon’ble Supreme Court records that the Aravali significantly influence climate regulation, groundwater recharge, biodiversity, and desertification control in North India.2

The difficulty arose from the nature of the Aravali itself. Being ancient and heavily eroded, large portions appear flat or gently sloping, even though they remain part of the same geological system. Visual identification and revenue records proved ill-suited to capture this continuity.

Historically, identification depended on revenue entries such as (i) Gair Mumkin Pahad (non-cultivable hill); or (ii) Banjar (wasteland); or (iii) Forest land. These records were never intended to reflect geological continuity since they varied from village to village, and often excluded eroded or flattened Aravali formations. As a net result, ARAVALI land escaped protection, while enforcement became selective and litigative.

The problem, therefore, was not scientific uncertainty, but administrative incoherence.

Early Judicial Protection and Its Structural Limits

[Figures 3 & 4: Landscape Reality of the Aravali

Representative ground-level imagery illustrating erosion, mining pressure, and the non-dramatic visual profile of many Aravali formations. Images sourced from open-access environmental documentation and news photography.]

Judicial engagement with the protection of the Aravali emerged prominently in the 1990s, particularly through environmental proceedings addressing illegal mining in Rajasthan and Haryana. The judicial engagement with the protection of the Aravali Hills emerged within the framework of two long-running environmental proceedings that have shaped Indian environmental jurisprudence.

The first, M.C. Mehta v. Union of India and others3,though originally instituted to address vehicular pollution in the National Capital Region, gradually expanded in scope to encompass issues of environmental degradation arising from mining activities in the Aravali Hills.

The second,T.N. Godavarman Thirumulpad v. Union of India and others4, initially concerned with forest conservation in the Gudalur region of Tamil Nadu, but evolved into a continuing mandamus exercising supervisory jurisdiction over forests, wildlife, and ecologically sensitive areas across the country.

The Supreme Court, within this jurisprudential framework, adopted robust protective measures, including the 2002 directions prohibiting mining in the Aravali Hills of Haryana.

These interventions were environmentally significant but structurally incomplete. They operated on case-specific facts and administrative classifications, without resolving the foundational question of how the Aravali system itself should be identified across States. As a result, protection depended largely on revenue records, forest classifications, and visually identifiable hills, which is an approach that proved inadequate for an ancient, eroded mountain system such as the Aravali.

The confusion surrounding the Aravali was legal and administrative, not scientific. Before the Hon’ble Supreme Court’s judgment:

- there was no statutory definition of “ARAVALI HILLS” or “ARAVALI RANGES”;

- States adopted divergent and inconsistent criteria; and

- Some states (notably Haryana) had no formal definition at all.5

The Supreme Court expressly records that definitional inconsistency itself became a facilitator of illegal mining and environmental degradation.6

Emergence of the 100-Metre Local-Relief Criterion

The conceptual foundation for using local relief rather than absolute elevation was developed through expert studies conducted by institutions such as the Forest Survey of India (‘FSI’) and the Geological Survey of India (‘GSI’) in the early 2000s. These studies recognised that many Aravali formations no longer exhibit dramatic height differences due to prolonged erosion yet remain geologically and ecologically integral to the range.

In this context, administrative guidelines and expert committee reports began using a 100-metre local-relief threshold as an operational indicator to identify hill formations within the Aravali system. Importantly, this threshold was not intended as a tool for exclusion, but as a scientific aid to distinguish hills from plains in terrain where absolute height above sea level was misleading.

The debate regarding the 100m-Rule intensified when the State of Rajasthan formally established a definition for regulating mining in the Aravali definition, which was based on the 2002 Committee Report of the State Government relying on Richard Murphy’s landform classification that identified all landforms rising 100m above local relief as hills and based on that, prohibiting mining on both the hills and its supporting slopes.

It is most pertinent to clarify herein that the State of Rajasthan has been following this definition since 9th January, 2006. During deliberations, all States agreed to adopt the aforementioned uniform criterion of “100 metres above local relief” for regulating mining in the Aravali region as had been in force in Rajasthan since 09.01.2006, while unanimously agreeing to make it more objective and transparent.

At the executive level, States such as Rajasthan and Haryana issued notifications and mining guidelines that variously referred to hill height, slope, and local relief, including references to the 100-metre criterion. However, these standards were applied inconsistently, often limited to specific districts or mining contexts, and were never consolidated into a uniform, pan-state definition. In several instances, the same landform was treated as an Aravali hill in one district and excluded in another. This lack of uniformity not only weakened environmental protection but also created fertile ground for illegal mining, selective enforcement, and prolonged litigation.

Reference to the Central Empowered Committee

The definitional uncertainty eventually reached the Supreme Court in ongoing environmental proceedings, particularly when disputes arose over whether specific mining activities fell within the Aravali Hills or outside them.

On 10th January 2024, the Court was confronted with conflicting claims by States and stakeholders regarding the classification of landforms within the Aravali region. The real issue before the Hon’ble Supreme Court was not deciding whether mining should be allowed. It was addressing a foundational question as to how the Aravali Hills and Ranges can be scientifically identified when States follow inconsistent criteria. The Court was hearing two sets of proceedings. First one in MC Mehta v. Union of India and others7 and another in T.N. Godavarman Thirumalpad v. Union of India and others8.

During the hearing on 10th January 2024, an issue arose for consideration before the Hon’ble Supreme Court as to whether some of the mining activities fell within the Aravali Hills or beyond it. On the said date, the learned Senior Counsel appearing for the State of Rajasthan raised an issue as to the classification between the Aravali Hills and Aravali Ranges insofar as mining activities are concerned, which needs to be finally decided by the Hon’ble Court. And on the same date, the learned Amicus Curiae raised an issue as to whether continuation of the mining activities in Aravali Hills and Ranges was in the larger public interest or not and further suggested that it would be appropriate if all the issues with regard to the Aravali Hills and Ranges be examined by the Central Empowered Committee (‘CEC’).

It is therefore, vide order dated 10.01.2024 in the proceedings, the Hon’ble Supreme Court requested the CEC to examine as to “whether the classification of Aravali Hills and Ranges, insofar as permitting mining is concerned, needs to be continued or not.”9 The CEC was further requested to take on board the experts in geology before finalising its report.

Thus, in pursuance of the order dated 10.01.2024 passed by the Hon’ble Supreme Court, the CEC submitted its report finally on 7th March 2024 (CEC Report No.3 of 2024).

Scientific Delineation of Hills and Ranges

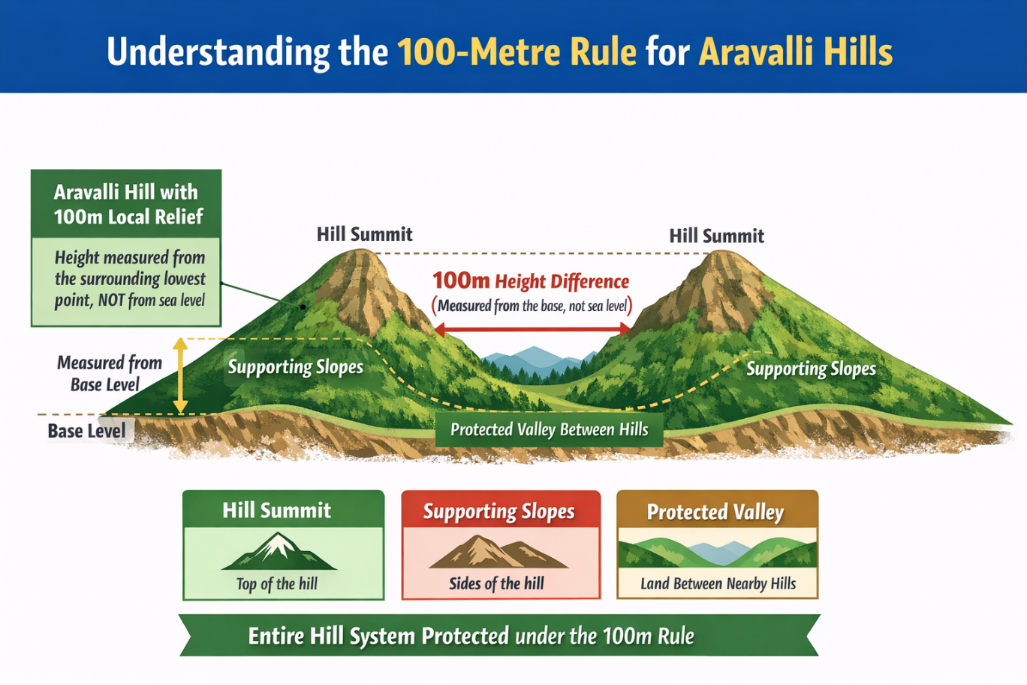

[Figure 5: Author’s Diagram — 100-Metre Local-Relief Criterion

An illustrative geomorphological representation explaining the “100-metre local-relief” method adopted by the Central Empowered Committee and accepted by the Supreme Court of India in In Re: Issue Relating to Definition of Aravali Hills and Ranges (2025 INSC 1338)]

The CEC, in its Report No.3 of 2024, recommended defining an “Aravali Hill” as any landform within the Aravali districts having a local relief of 100 metres or more, measured from the lowest contour line encircling the landform, and not from mean sea level.

Crucially, the definition extends beyond hilltops to include supporting slopes, associated landforms and inter-hill valleys. Further, where two or more such hills lie within 500 metres of each other, the entire intervening area is treated as part of an “Aravali Range”. This continuity-based framework prevents artificial fragmentation of the ecosystem and closes a long-standing enforcement loophole.

Operative Directions of the Judgment

The Supreme Court’s operative directions highlight the environmental orientation of the decision. The Court:

- prohibited the grant of new mining leases until a Management Plan for Sustainable Mining (MPSM) is prepared10;

- mandated geo-referenced ecological assessment by expert bodies such as ICFRE;

- prohibited mining in core, inviolate, wildlife and eco-sensitive zones; and

- permitted existing mining operations to continue only under strict regulatory compliance.11

Significantly, the Court declined to impose a blanket ban, consistent with its jurisprudence recognising that unscientific prohibitions often fuel illegal mining rather than conservation.

Part-C – Doctrinal Defence & Implications

Precautionary Principle and Public Trust Doctrine

A common criticism is that the judgment does not expressly invoke the ‘precautionary principle’ or the ‘public trust doctrine’ to impose a total ban on mining. This critique rests on the flawed assumption that these doctrines mandate absolute prohibition.

Indian environmental jurisprudence treats these principles as tools of governance whose application is context-specific and informed by scientific evidence. In the present case, the Court was addressing a threshold governance failure, the absence of a scientifically coherent method for identifying the Aravali system. Invoking doctrinal prohibitions without resolving this ambiguity would have risked uneven enforcement and increased illegality.

The public trust obligation is instead embedded structurally through recognition of ecological continuity, imposition of State stewardship duties, and a freeze on new mining pending expert planning.

The 100-Metre Rule is not an Exclusionary Cut-Off

A commonly held assumption, including one initially shared by the present author prior to a careful reading of the judgment, is that landforms below 100 metres of local relief are excluded from protection. This is absolutely incorrect.

As mentioned earlier in PART-B (VII) hereinabove, even where a landform does not independently satisfy the 100-metre criterion, it remains protected if it constitutes a supporting slope, an associated landform, or an inter-hill valley between qualifying hills. Large contiguous areas below 100 metres, therefore, continue to fall within the definition of an “Aravali Range”.

Post-Judgment Developments and Continuing Oversight

The aftermath of the judgment was marked by a wave of public controversy that bore little correlation to the actual reasoning or operative directions of the decision.12 Selected media reportage and social-media commentary propagated the misleading narrative that the Supreme Court had “permitted mining” in the Aravali Hills by introducing the 100-metre criterion, resulting in protests and public demonstrations in parts of Rajasthan and Delhi.13

Much of this criticism was driven by headline-centric interpretations rather than engagement with the judgment’s text, which in fact freezes new mining leases and mandates scientific zoning through a Management Plan for Sustainable Mining.

Following public controversy, the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change clarified that the judgment does not permit indiscriminate mining and that over 99% of the Aravali region continues to remain regulated under existing environmental laws, forest protections and eco-sensitive zone norms.14

In an extraordinary development, a former Chief Justice of India publicly addressed these misconceptions in a televised interview, clarifying that the Court had neither created a new permissive rule nor granted any mining licence, and that the 100-metre local-relief criterion was a scientific, operational tool adopted on expert recommendation.

Suo motu cognisance and continuing mandate of Environmental Protection

Amidst these developments, the Supreme Court has taken suo motu cognisance of the controversy and heard the matter on 29.12.2025, underscoring the continuing judicial engagement with protecting the Aravali ecosystem. The bench, comprising the Hon’ble Chief Justice of India Justice Surya Kant, Justice JK Maheshwari and Justice AG Masih, by the order dated 29.12.2025, stayed the earlier judgment dated 20.11.202515, observing that the report of the CEC and certain resultant observations in the judgment have “generated misunderstood notions” and required clarification.

The Court further observed that there was a need to examine whether the restrictive demarcation approved last month would broaden the scope of areas for mining and proposed to constitute a high-powered expert committee to resolve ambiguities and to provide definitive guidance on the issues concerning Aravali, particularly the definitions of “Hills” and “Ranges”. Notice has also been issued to the Union of India as well as the concerned State Governments, and the matter has been directed to be listed on 21.01.2026 before the Green Bench.

Consequently, the Court kept the Committee’s Report and related directions in its judgment dated 20.11.2025 in abeyance, pending expert evaluation, and mandated prior judicial permission for all mining activities in areas previously defined as Aravali Hills and Ranges.

The Court’s continued engagement underscores that the judgment is not the end of judicial oversight, but part of an evolving process of environmental supervision aimed at ensuring faithful implementation of its ecological mandate.

Conclusion

The Aravali definition judgment represents a scientifically anchored clarification rather than a deregulatory shift. It replaces fragmented, visual and record-based classifications with a geomorphology-based framework that strengthens ecological protection while constraining administrative discretion.

Properly understood, the decision reflects judicial restraint in service of environmental constitutionalism, privileging scientific method over symbolism and institutional accountability over headline-driven absolutism.

References:

- In Re: Issue Relating to Definition of Aravali Hills and Ranges; 2025 INSC 1338. ↩︎

- Id at para 2–4. ↩︎

- M.C. Mehta v. Union of India and others; W.P.(C) No. 4677 of 1985. ↩︎

- T.N. Godavarman Thirumulpad v. Union of India and others; W.P.(C) No. 202 of 1995. ↩︎

- In Re: Issue Relating to Definition of Aravali Hills and Ranges; 2025 INSC 1338 [I.A. No.105701/2024 (CEC Report No. 03 /2024) in Writ Petition (C) NO.202/1995] at para 21. ↩︎

- Id at para 11–14. ↩︎

- M.C. Mehta v. Union of India and others; W.P.(C) No. 4677 of 1985. ↩︎

- T.N. Godavarman Thirumulpad v. Union of India and others; W.P.(C) No. 202 of 1995. ↩︎

- In Re: Issue Relating to Definition of Aravali Hills and Ranges, 2025 INSC 1338 at para 13. ↩︎

- Id at paras 42–46. ↩︎

- Id at para 45–50. ↩︎

- https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/delhi/jnu-students-march-against-new-aravali-definition-call-for-strong-legal-safeguards/articleshow/126208486.cms? ↩︎

- https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/jaipur/thousands-embark-on-4-km-march-to-protect-ranges/articleshow/126219318.cms? ↩︎

- https://www.pib.gov.in/FactsheetDetails.aspx?ModuleId=16&NoteId=150596&id=150596&lang=1®=3&utm_source=chatgpt.com ↩︎

- Order dated 29.12.2025 in Suo Moto Writ Petition (C) No. 10/2025; In Re: Definition of Aravalli Hills and Ranges and Ancillary Issues ↩︎

By entering the email address you agree to our Privacy Policy.