Circumstantial Evidence In Criminal Cases: Principles For Examination

Introduction

Circumstantial evidence does not provide direct proof but pieces together facts that lead to a clear conclusion. Recently, in Abdul Nassar v. State of Kerala, the Supreme Court (SC) reinforced how crucial this type of evidence can be in criminal trials.[1] The Court upheld the conviction, emphasizing that when a series of events point only to the accused’s guilt, it can be just as powerful as eyewitness testimony. This case reaffirmed the legal principles for evaluating circumstantial evidence in serious offenses.

Table of Contents

What is Circumstantial Evidence?

Understanding Circumstantial Evidence

- Circumstantial evidence refers to evidence that relies on inference instead of directly proving a fact. It establishes a series of events or a chain of circumstances which point toward a logical conclusion.

- In legal proceedings, especially criminal proceedings, circumstantial evidence plays an important role. This is especially when direct evidence is either unavailable or insufficient to prove a fact or the accused’s guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. Courts usually rely on circumstantial evidence if there exist no eyewitnesses to an incident but there are enough surrounding facts to point towards what is likely to have occurred.

- Indian courts have consistently held that circumstantial evidence can be as valid and compelling as direct evidence if it presents a complete and unbroken chain that leads only to one conclusion, which is the guilt or liability of the accused.

Legal Definition and Recognition of Evidence

- Section 3 of the Indian Evidence Act (IEA), 1872 defines evidence as:

- Oral Evidence: Statements made by witnesses that the court permits or requires in relation to facts under inquiry.

- Documentary Evidence: Documents, including electronic records, produced before the court for inspection.

- The recently enacted Bhartiya Sakshya Adhiniyam, 2023 (BSA) also contains a similar recognition of evidence. Section 2(k) defines “relevance” based on the evidence’s connection to other facts.

- Under Indian law, there are broadly two categories of evidence:

- Direct Evidence: This conclusively establishes a fact without the need to draw an inference.

- Circumstantial Evidence: This relies on logical inferences arising from a chain of events to prove an assertion.

Difference between Direct and Circumstantial Evidence

- Nature of Proof: Direct evidence proves a fact conclusively and unequivocally. On the other hand, circumstantial evidence leads to a conclusion based on inference.

- Need for Interpretation: Direct evidence does not need to be interpreted because it speaks for itself. For instance, an eyewitness’s testimony regarding the crime. Circumstantial evidence, however, needs reasoning and inference to connect different facts and draw a conclusion.

- Common Examples:

- Direct Evidence: A person who testifies that they saw the accused commit a crime.

- Circumstantial Evidence: Fingerprints, DNA traces, or CCTV footage that place the accused at the scene of the crime. All of these require reasoning and inference to draw a conclusion.

- Judicial Weight: Generally, courts give more weight to direct evidence. However, circumstantial evidence can also be equally strong if it forms a clear and unbroken chain of events that leads to only one possible conclusion.

- Corroboration Requirement: Direct evidence does not usually need much corroboration because it directly proves a fact. On the other hand, circumstantial evidence often requires multiple other facts which support such evidence to enhance its credibility.

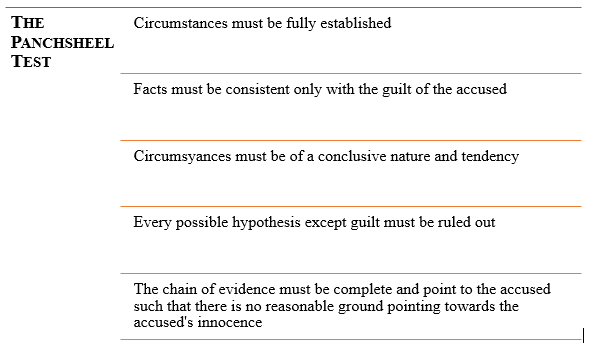

The Panchsheel Test: Sharad Birdhichand Sarda

In Sharad Birdhichand Sarda v. State of Maharashtra, the SC laid down the Panchsheel test for the examination of circumstantial evidence in a case.[2] These are often referred to as the five golden principles that are needed to be satisfied before a court convicts an accused by relying on circumstantial evidence. These are as follows:

Other landmark Decisions

- Anwar Ali v. State of Himachal Pradesh: This case clarified how motive plays a role in circumstantial evidence.[3] While proving a motive strengthens the prosecution’s argument, its absence is not enough to dismiss the case. The court emphasized that motive is just one factor in the broader chain of evidence, not the deciding factor. Referring to Suresh Chandra Bahri[4] and Babu v. State of Kerala[5], the judgment highlighted the need for a balanced approach when evaluating motive in such cases.

- Nagendra Shah v. State of Bihar: Here, the Supreme Court reinforced the significance of Section 106 of the IEA.[6] If an accused cannot offer a reasonable explanation for incriminating circumstances, it can serve as an additional link in the prosecution’s case. However, the decision clarified that this alone was not sufficient proof of guilt but rather only one of the factors to be assessed by the court while determining culpability.

- Dilip Sariwan v. State of Chhattisgarh: This case involved a murder conviction based primarily on circumstantial evidence regarding an extramarital affair.[7] The court stressed that in cases like these, every link in the chain of circumstances must be proved beyond reasonable doubt. It also underscored the role of Section 27 of the IEA, which governs the admissibility of certain confessions and disclosures, reaffirming the high standard of proof required for circumstantial evidence to hold weight in court.

- Balvir Singh v. State of Uttarakhand: The decision in this case clarified that Section 106 of the IEA cannot be used as a shortcut to conviction.[8] The court held that a full trial is necessary, and merely shifting the burden of proof onto the accused without due process is not acceptable. The judgment reinforced the principle that while unexplained circumstances may raise suspicion, they cannot replace a thorough and fair trial.

Supreme Court’s Recent Decision: Abdul Nassar v. Kerala[9]

Background of the Case

- The case involves the heinous rape and murder of a 9-year-old girl in Kerala.

- The victim had left home at around 6:30 AM to attend Madrassa and stopped at the house of the accused, Abdul Nassar, to meet his daughter.

- The accused, who was alone at home, committed the crime and tried to dispose of the body. A search was initiated when the victim did not return home, and her body was found hidden beneath clothes in the bathroom of the accused’s house around 7:30 PM.

- The trial court convicted Abdul Nassar under Sections 302 (murder) and 376 (rape) of the Indian Penal Code (IPC), awarding him the death sentence and 7 years of rigorous imprisonment.

- The High Court confirmed the death sentence, which led to an appeal before the SC.

Court’s Decision and Reasoning

- The Supreme Court reaffirmed the conviction and upheld the circumstantial evidence, concluding that the prosecution had established an unbroken chain of events proving guilt beyond a reasonable doubt.

- The five-pronged test from Sharad Birdhichand Sarda, as explained above, was applied.

- The chain of events as observed by the SC was as follows:

- The victim, a friend of the accused’s daughter, regularly went to Madrassa with her. On the morning of the incident, she left home but never reached the Madrassa, making the accused’s house the last known location linked to her disappearance.

- Since the victim was last seen near the accused’s house, repeated search attempts were made. The house was locked during the first two searches, raising doubts about the accused’s whereabouts and actions.

- When the accused was found sitting on his veranda during the third search attempt, he falsely claimed he had been out searching for the victim. He refused to open his house, saying the keys were with his wife, further intensifying suspicion.

- The victim’s body was eventually found hidden under a heap of clothes in the accused’s bathroom. Two stones from the septic tank inside his house were found displaced, indicating an attempt to dispose of the body.

- Blood stains matching the victim’s DNA were found on the cot and the floor. Her underwear was recovered from the accused’s kitchen. DNA analysis confirmed that semen stains on her clothing and vaginal swabs matched the accused, linking him directly to the crime.

- The victim’s personal belongings, including her slippers, writing pad, pen, and plastic bag, were recovered from the accused’s house, proving her presence there. The postmortem report revealed 37 antemortem injuries, confirming sexual assault and strangulation as the cause of death.

- The SC ruled that the circumstantial evidence formed an unbroken chain pointing solely to the accused’s guilt. The defence’s claims of evidence tampering were rejected, and the court upheld the conviction based on the “last seen together” principle, forensic evidence, and the accused’s misleading conduct.

Conclusion

Circumstantial evidence often becomes the deciding factor in criminal trials, particularly when direct evidence is not available. However, courts do not accept it lightly. It is relied upon only if it forms a clear, logical sequence that leaves no room for doubt and points only towards the guilt of the accused. Over the years, decisions like Sharad Birdhichand Sarda and Abdul Nassar have shaped how such evidence is assessed, ensuring justice is not based on guesswork. The challenge lies in striking the right balance: holding the guilty accountable while safeguarding the accused from wrongful conviction.

[1] https://api.sci.gov.in/supremecourt/2018/16719/16719_2018_6_1503_58315_Judgement_07-Jan-2025.pdf.

[2] Sharad Birdhichand Sarda v. State of Maharashtra, (1984) 4 SCC 116.

[3] Anwar Ali v. State of Himachal Pradesh, AIR 2020 SC 4519.

[4] Suresh Chandra Bahri v. State of Bihar, 1995 Supp (1) SCC 80.

[5] Babu v. State of Kerala, (2010) 9 SCC 189.

[6] Nagendra Shah v. State of Bihar, Criminal Appeal No. 1903/2019.

[7] https://highcourt.cg.gov.in/hcbspjudgement/judgements_web/CRA191_23(20.08.24)_6.pdf.

[8] https://digiscr.sci.gov.in/admin/judgement_file/judgement_pdf/2023/volume%2012/Part%20I/2023_12_815-852_1703055885.pdf.

[9] https://api.sci.gov.in/supremecourt/2018/16719/16719_2018_6_1503_58315_Judgement_07-Jan-2025.pdf

King Stubb & Kasiva,

Advocates & Attorneys

New Delhi | Mumbai | Bangalore | Chennai | Hyderabad | Mangalore | Pune | Kochi

Tel: +91 11 41032969 | Email: info@ksandk.com

By entering the email address you agree to our Privacy Policy.